Okay you Dead Beats you need to read and digest this - you may have read it before but trust me you did not digest it:

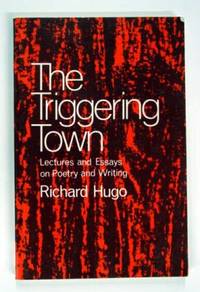

"The Triggering Town"from The Triggering Town

by Richard Hugo

You hear me make extreme statements like "don't communicate" and "there is no reader."While these statements are meant as said, I presume when I make them that you can communicate and can write clear English sentences. I caution against communication because once language exists only to convey information, it is dying.Let's take language that exists to communicate--the news story. In a news story the words arethere to give you information about the event. Even if the reporter has a byline, anyone might have written the story, and quite often more than one person has by the time it is printed. Once you have the information, the words seem unimportant. Valery said they dissolve, but that's not quite right.Anyway, he was making a finer distinction, one between poetry and prose that in the reading of English probably no longer applies. That's why I limited our example to news articles. By understanding the words of a news article you seem to deaden them.In the news article the relation of the words to the subject (triggering subject since there is no other unless you can provide it) is a strong one. The relation of the words to the writer is so weak that for our purposes it isn't worth consideration. Since the majority of your reading has been newspapers, you are used to seeing language function this way. When you write a poem these relations must reverse themselves. That is, the relation of the words to the subject must weaken and the relation of the words to the writer (you) must take on strength. This is probably the hardest thing about writing poems. It may be a problem with every poem, at least for a long time. Somehow you must switch your allegiance from the triggering subject to the words. For our purposes I'll use towns as examples. The poem is always in your hometown, but you have a better chance of finding it in another. The reason for that, I believe, is that the stableset of knowns that the poem needs to anchor on is less stable at home than in the town you've just seen for the first time out home, not only do you know that the movie house wasn't always there, or that the grocer is a newcomer who took over after the former grocer committed suicide, you have complicated emotional responses that defy sorting out. With the strange town, you can assume all knowns are stable, and you owe the details nothing emotionally. However, not just any town will do. Though you've never seen it before, it must be a town you've lived in all your life.You must take emotional possession of the town and so the town must be one that, for personalreasons I can't understand, you feel is your town. In some mysterious way that you need not and probably won't understand, the relationship is based on fragments of information that are fixed and if you need knowns that the town does not provide, no trivial concerns such as loyalty to truth, a nagging consideration had you stayed home, stand in the way of your introducing them as needed by the poem. It is easy to turn the gas station attendant into a drunk. Back home it would have been difficult because he had a drinking problem.

Once these knowns sit outside the poem, the imagination can take off from them and if necessary can return. You are operating from a base.

That silo, filled with chorus girls and grain

Your hometown often provides so many knowns (grains) that the imagination cannot free itself to seek the unknowns (chorus girls). I just said that line (Reader: don't get smart. I actually did just write it down in the first draft of this) because I come from a town that has no silos, no grain,and for that matter precious few chorus girls. If you have no emotional investment in the town, though you have taken immediate emotional possession of it for the duration of the poem, it may be easier to invest the feeling in the words. Try this for an exercise: take someone you emotionally trust, a friend or a lover, to a town you like the locals of but know little about, and show your companion around the town in the poem. In the line of poetry above, notice the word "that." You are on the scene and you are pointing. You know where you are and that is a source of stability. "The silo" would not tell you where you were or wherethe silo is. Also, you know you can trust the person you are talking to--he or she will indulge your flights-- another source of stability and confidence. If you need more you can even imagine that an hour before the poem begins you received some very good news--you have just won a sweepstakes and will get $10,000 a year for the rest of your life--or some very bad, even shattering news--your mother was in charge of a Nazi concentration camp. But do not mention this news in the poem. That will give you a body of emotion behind the poem and will probably cause you to select only certain details to show to your friend. A good friend doesn't mind that you keep chorus girls in a silo. The more stable the base the freer you are to fly from it in the poem.

That silo, filled with chorus girls and grain burned down last night and grew back tall. The grain escaped to the river. The girls ran crying to the moon. When we knock, the metal gives a hollow ring--

O.K. I'm just fooling around. (God, I'm even rhyming.) It looks like the news I got an hour ago was bad, but note the silo replaced itself and we might still fill it again. Note also that now the town has a river and that when I got fancy and put those girls on the moon I got back down to earth in a hurry and knocked on something real. Actually I'm doing all this because I like "1" sounds, "silo" "filled""girls" "tall" "metal" "hollow," and I like "n" sounds, "grain" "burned" "down" "ran" "moon," "ring,"and I like "k" sounds, "back" "knock." Some critic, I think Kenneth Burke, would say I like "k" soundsbecause my name is Dick. In this case I imagined the town, but an imagined town is at least as real as an actual town. If it isn't you may be in the wrong business. Our triggering subjects, like our words, come from obsessions we must submit to, whatever the social cost. It can be hard. It can be worse forty years from now if you feel you could have done it and didn't. It is narcissistic, vain, egotistical, unrealistic, selfish, and hateful to assume emotional ownership of a town or a word. It is also essential.This gets us to a somewhat tricky area. Please don't take this too seriously, but for purposes of discussion we can consider two kinds of poets, public and private. Let's use as examples Auden and Hopkins. The distinction (not a valid one, I know, but good enough for us right now) doesn't lie in the subject matter. That is, a public poet doesn't necessarily write on public themes and the private poet on private or personal ones. The distinction lies in the relation of the poet to the language. With the public poet the intellectual and emotional contents of the words are the same for the reader as for the writer. With the private poet, and most good poets of the last century or so have been private poets, the words, at least certain key words, mean something to the poet they don't mean to the reader. A sensitive reader perceives this relation of poet to word and in a way that relation--the strangeway the poet emotionally possesses his vocabulary is one of the mysteries and preservative forces of the art. With Hopkins this is evident in words like "dappled," "stippled," and "pied." In Yeats,"gyre." In Auden, no word is more his than yours. The reason that distinction doesn't hold, of course, is that the majority of words in any poem are public--that is, they mean the same to writer and reader. That some words are the special property of a poet implies how he feels about the world and about himself, and chances are he often fights impulses to sentimentality. A public poet must always be more intelligent than the reader, nimble, skillful enough to stay ahead, to be entertaining so his didacticism doesn't set up resistances; Auden was that intelligent and skillful and he publicly regretted it. Here, in this room, I'm trying to teachyou to be private poets because that's what I am and I'm limited to teaching what I know. As a private poet, your job is to be honest and to try not to be too boring. However, if you must choose between being eclectic and various or being repetitious and boring, be repetitious and boring. Most good poets are, if read very long at one sitting.If you are a private poet, then your vocabulary is limited by your obsessions. It doesn't bother me that the word "stone" appears more than thirty times in my third book, or that "wind" and "gray"appear over and over in my poems to the disdain of some reviewers. If I didn't use them that often I'd be lying about my feelings, and I consider that unforgivable. In fact, most poets write the same poem over and over. Wallace Stevens was honest enough not to try to hide it. Frost's statement that he tried to make every poem as different as possible from the last one is a way of saying that he knew it couldn't be.So you are after those words you can own and ways of putting them in phrases and lines that are yours by right of obsessive musical deed. You are trying to find and develop a way of writing that will be yours and will, as Stafford puts it, generate things to say.

Your triggering subjects are those that ignite your need for words. When you are honest to your feelings, that triggering town chooses you. Your words used your way will generate your meanings. Your obsessions lead you to your vocabulary. Your way of writing locates, even creates, your inner life. The relation of you to your language gains power. The relation of you to the triggering subject weakens. The imagination is a cynic. By that I mean that it can accommodate the most disparate elements with no regard for relative values. And it does this by assuming all things have equal value, whichis a way of saying nothing has any value, which is cynicism.When you see a painting by Hieronymus Bosch your immediate impression may be that he was a weirdo. A wise man once told me he thought Bosch had been a cynic, and the longer I thought about this the truer it seemed. My gold detector told me that the man had been right. Had Bosch concerned himself with the relative moral or aesthetic values of the various details, we would see more struggle and less composure in the paintings themselves. The details may clash with each other, but they do not clash with Bosch. Bosch concerned himself with executing the painting--he must have--and that freed his imagination, left him unguarded. If the relative values of his details crossed his mind at all while he was painting, he must have been having one hell of a good time.One way of getting into the world of the imagination is to focus on the play rather than the value of words--if you can manage it you might even ignore the meanings for as long as you can, though that won't be very long. Once, picking up on something that happened when I visited an antique store in Ellettsville, Indiana, I wrote the lines

The owner leaves her beans to brag about the pewter. Miss Liberty is steadfast in an oval frame.

They would have been far harder lines to write had I worried about what's most important: beans, pewter, or liberty. Obviously beans are, but why get hung up on those considerations? It is easier to write and far more rewarding when you can ignore relative values and go with the flow and thrust of the language.

That's why Auden said that poets don't take things as seriously as other people. It was easy for me to find that line awhile back because I didn't worry about the relative importance of grain and chorus girls and that made it fun to find them together in that silo.By now you may be thinking, doesn't this lead finally to amoral and shallow writing? Yes it does, if you are amoral and shallow. I hope it will lead you to yourself and the way you feel. All poets I know, and I know plenty of them, have an unusually strong moral sense, and that is why they can go into the cynical world of the imagination and not feel so threatened that they become impotent. There's fear sometimes involved but also joy, an exhilaration that can't be explained to anyone who has not experienced it. Don't worry about morality. Most people who worry about morality ought to. Over the years then, if you are a poet, you will, perhaps without being conscious of it, find a way to write--I guess it would be better to say you will always be chasing a way to write. Actually, you never really find it, or writing would be much easier than it is. Since the method you are chasing involves words that have been chosen for you by your obsessions, it may help to use scenes (towns perhaps) that seem to vivify themselves as you remember them but in which you have no real emotional investment other than the one that grows out of the strange way the town appeals to you,the way it haunts you later when you should be thinking about paying your light bill. As a beginner you may only be able to ally your emotions to one thing, either triggering subject or word. I believeit will be easier right now if you stick to the word. A man named Buzz Green worked with me years ago at the Boeing Company. He had once been a jazz musician and along with a man named Lu Waters had founded a jazz band well known in its day. Buzz once said of Lou McGarrity, a trombone player we both admired, "He can play trombone with any symphony orchestra in the country but when he stands up to take a jazz solo he forgets everything he knows." So if I seem to tank technique now and then and urge you to learn more, it is not so you will remember it when you write but so you can forget it. Once you have a certain amount of accumulated technique, you can forget it in the act of writing. Those moves that are naturally yours will stay with you and will come forth mysteriously when needed. Once a spectator said, after Jack Nicklaus had chipped a shot in from a sand trap, "That's prettylucky." Nicklaus is supposed to have replied, "Right. But I notice the more I practice, the luckier I get." If you write often, perhaps every day, you will stay in shape and will be better able to receivethose good poems, which are finally a matter of luck, and get them down. Lucky accidents seldom happen to writers who don't work. You will find that you may rewrite and rewrite a poem and itnever seems quite right. Then a much better poem may come rather fast and you wonder why youbothered with all that work on the earlier poem. Actually, the hard work you do on one poem is put inon all poems. The hard work on the first poem is responsible for the sudden ease of the second.If you just sit around waiting for the easy ones, nothing wild come. Get to work.You found the town, now you must start the poem. If the poem turns out good, the town will have become your hometown no matter what name it carries. It will accommodate those intimatehunks of self that could live only in your hometown. But you may may have found those hunksof self because the externals of the triggering town you used were free of personal association and were that much easier to use. That silo you never saw until today was yours the day you were born. Finally, after a long time and a lot of writing, you may be able to go back armed to places of realpersonal significance. Auden was wrong. Poets take some things far more seriously than other people, though he was right to the extent that they are not the same things others would take seriouslyor often even notice. Those chorus girls and that grain really matter, and it's not the worst thing you can do with your life to live for that day when you can go back home the sure way and find they were there all the time.

.jpg)